- Home

- Sarah Hawkswood

Marked to Die Page 8

Marked to Die Read online

Page 8

Bradecote was vaguely shocked. The man thought like a merchant. Of course, it was good to have spare silver to purchase things but this sounded like a man to whom ‘profit’ meant more than ‘honour’.

‘So do you know the culprits you seek?’ Rannulf de Lasson spoke as if to a menial.

‘As yet, my lord de Lasson, no.’

‘Then,’ de Lasson sneered, ‘I suggest you get about your business, rather than linger doing nothing here.’

With which he yanked his horse’s head around and trotted away.

There was silence. Walkelin studied the muddy earth, since lordly arguments were above him. Catchpoll scratched his ear and the reeve feigned deep interest in a woman arguing with a man over a chicken, which was dangling by its feet from her hand.

Bradecote did not look at the receding figure. He fought his anger, and when his pulse was steady, addressed the reeve.

‘As I was saying, finding this horse is very important, Master Reeve. If any have seen it within Wich or upon the roads, we will hear of it or I will be asking why not, and of you personally. Now, direct us to the salt houses involved thus far, those of Alcester, Bordesley, and Baldwin de Malfleur.’

The reeve, glad to see a chance of escape, almost fell over himself in an effort to be of help leading them to the salt houses belonging to the monks at Bordesley. The workers, bare-armed and sweating though the world outside was chill, were suspicious of the undersheriff. Those in authority were bound to find fault and want a better rate of work. Walkelin and Catchpoll, however, slipped into conversation easily, Walkelin helping a comely if slightly overblown young woman move wicker baskets of warm, damp salt to drain. Seeing that his presence was less than helpful, Bradecote withdrew, after a murmured exchange with Catchpoll.

Out in the clear air, he took a deep breath. He was tying himself in knots, unsure where to head next, and at the back of his mind was the look of fear on Christina FitzPayne’s face. It made him feel sick to think she thought him capable of violence upon her. At the same time he knew he should not be thinking of her at all. She was clouding his brain. There was a tavern opposite, out of the wind, and yet not, he hoped, smelling of brine, or indeed tasting of it, as Catchpoll had complained at an alternative alehouse.

On this occasion he was spared both. The host, almost grovelling in his obeisance at the presence of such a personage, brought him an ale worth the supping, and which drew an honest compliment. The man went quite pink with pride.

‘Well, ’tis kind of my lord to say such, but I pride myself on the quality of my ale, and those who care what they drink, drink here. Master Reeve does, of course, in his position, but to be truthful, after the first jug, he could not care less about the taste.’

‘I’ll vouch for its quality, to any who might ask, but in truth I am not likely to be asked.’

He saw Walkelin and Catchpoll enter, and ordered ale for each. Walkelin looked a little green about the gills.

‘I never knew they used blood as well as …’ Walkelin swallowed hard.

‘Thought it would not affect you after the visit to the tanner,’ Catchpoll commented, grinning.

‘We don’t put the leather on our food.’

‘True enough.’

‘I’m not sure I can face Mother’s salted pork she has hanging, after that.’

Walkelin shook his head, mournfully.

‘Oh, you will lad, you will, when she serves it up on a cold winter evening with apples and onions.’

‘Put that way, Sergeant,’ Walkelin managed a grin, ‘I might after all.’

‘So did we learn anything useful other than how they make salt?’ Bradecote sounded wry rather than irritated, and Catchpoll hoped the ale had eased his superior’s mood. He pulled a face and tugged an earlobe.

‘Not so as we could say so, my lord. I would doubt very much if the information came from the simple workers in the salt houses. They do not seem to know exactly when the salt departs. They just keep making it day after day.’

‘So who decides when it goes? It cannot be upon whim.’ Bradecote wished that something would be simple.

‘It seems, my lord, that when there is enough for a load, which has to either pay toll or show exemption, the salt house sends to inform the reeve who collects the payment, and goes to the packmen or sends to the lord for him to send his own wagon. De Malfleur sent a wagon, but the religious houses used the Wich packmen.’

‘So only the reeve has the knowledge of what is leaving?’ The undersheriff was vaguely hopeful.

‘Wish it were that simple, my lord.’ Catchpoll was at his most lugubrious. ‘Thing is, everyone in Wich knows everyone else. Many lords and abbeys have more than one salt house, so they work together. If a load was near ready, half the town would be in the know of it for days beforehand, and the packmen know their next run.’

Bradecote swore, softly but impressively, in English. Catchpoll smiled.

‘There’s nothing in Foreign can beat swearing in the native tongue, not for getting it out the system, so to speak.’

‘But it does not make us any nearer an answer, Catchpoll,’ Bradecote sighed.

‘As we came in we did see the reeve flitting like a bee to flowers in summer, passing on the need to know about the horse, though, my lord.’ Walkelin wanted to be positive.

‘Somehow I do not think we will learn much more this afternoon.’ Bradecote sighed. ‘We might as well return to the manor, I suppose.’

Walkelin grinned. Bradecote could not be as cheerful. After all, Walkelin’s return to Cookhill meant fresh baking and making eyes at the goat girl, whereas he faced a frosty reception from a woman who might well throw things at his head. What made it perhaps worse was that a little voice inside him was shouting that seeing her angry was better than not seeing her at all. He felt he was sliding down a slippery slope, losing control, and it was all at the wrong time and in the wrong place. He had to concentrate upon the investigation, not be distracted by a woman who seemed intent on driving him mad, with both anger and, if he was honest, deep-seated longing.

‘The trouble is,’ muttered the undersheriff gloomily, ‘I fear we are merely waiting for another attack, not preventing one.’

They retrieved their horses and were on the point of departure when the clatter of hooves made them turn. Eight men-at-arms, mailed and clearly trying to impress, cantered into the middle of the main thoroughfare. They each wore the badge of de Malfleur, the black flower upon scarlet. They were, as they had intended, the centre of attention. Catchpoll sneered, but conceded that however obvious, it was just the show of force de Malfleur would wish.

‘Come to show off the advantages of their lord’s protection. If you was a packman, you would be hoping they would escort you. Bully boys, mind, just look at ’em.’

‘They cannot stop an arrow, Serjeant.’ Walkelin sounded pious.

‘Oh, many a man-at-arms has stopped an arrow, young Walkelin.’ Catchpoll grinned at his own sally.

‘But I meant …’

‘I know what you meant, and you are correct, but even a good archer will not choose to take on trained soldiers, when there are easier options. No, those who pay will be safe enough.’

They trotted off upon the Salt Road, with hardly anyone watching them, though one who did smiled.

Chapter Seven

The sun was making sporadic attempts to pierce the cloud, but its sallow rays did not offset the chill of the wind, which still tugged at the remaining leaves, beggar’s tatters upon beech, ash and oak. The occasional rising swirl of rattling leaves would spook one of the horses, but not so as to unseat the rider. They arrived at Cookhill with several hours of labour still left in the day, and found it busy. Walkelin took the horses to the stables to attend to them, and Bradecote and Catchpoll mounted the steps to the hall. It was only at this point that Bradecote realised that he had not informed the serjeant of the theft of the arrows from his bags. He was not sure how he wished to impart this information, and was still pond

ering it when they entered the hall and found lady FitzPayne entertaining a visitor, whose back was towards them. Bradecote felt uncomfortable, recognising that he had entered as one with a right to do so, not as a guest. The look she gave him told him what she thought of it, but her voice, which he had expected to be most unfriendly, was distinctly warm, and had an edge of relief to it.

‘My lord Bradecote, you are returned.’

He frowned at her statement of the blindingly obvious. The man who had been sitting with her, engaged in some earnest conversation, turned. He was not known to Bradecote.

‘My lord Jocelyn, this is the lord Undersheriff of the shire, who currently enjoys my hospitality,’ she invested the term with deeper meaning, and lowered her gaze bashfully for a moment, ‘whilst he hunts my husband’s murderer, and, er, Serjeant Catchpoll, his … serjeant.’

Again, Bradecote wondered at her manner of speech, and his dark brows drew together.

‘This, my lord Undersheriff, is my lord’s cousin, Jocelyn of Shelsley, come to offer condolences upon my loss, and assistance, since I am but “a tragic, weak woman”.’

Even Catchpoll looked astounded at her description of herself, though Bradecote could hear the dripping sarcasm and was almost tempted to laugh. He looked at the man. He was about a dozen years Bradecote’s senior, with white hairs in his beard and greying locks, and with a look of sincere concern that Bradecote found quite sickly. The lady’s change of attitude was now explained. Failing to catch the undertone, Jocelyn of Shelsley leant forward and patted the widow’s hand. Christina looked at Bradecote. It was a warning, which said if there was so much as a hint of a laugh he would pay dearly. She smiled at her husband’s kinsman, and he was apparently quite impervious to its forced sweetness. Bradecote was quite bemused. The man was either an almighty fool, or supremely confident of his own importance. No, in fact, he was probably both.

‘My lord, I am sure the lady FitzPayne is grateful for your kindness in visiting her in her grief. She has,’ Bradecote paused for a moment, ‘managed, managed well, but to know that you are … on hand, must be very … reassuring.’

‘Indeed. She will be able to rely upon me to guide her, until Corbin’s brother returns, if indeed he is able to do so.’

So that was the underlying reason for his concern. The good Jocelyn had hopes of controlling the manor, if Corbin’s heir was dead in the East, and with the youngest brother choosing the cowl over the secular world.’ Bradecote thought he would find the lady had her own ideas on that.

‘The lord of Shelsley is remaining here for the night.’ Christina FitzPayne spoke through nearly gritted teeth.

‘Or longer, dear lady, if needed.’

Catchpoll noted the lady’s knuckles showing white as her fists clenched. She ignored the comment.

‘So there will be three of us to eat tonight, my lord Bradecote.’ She stared at him. He had not looked forward to a meal with glowering looks that would poison his meat, but this might be worse. He murmured a lie of pleasure.

Catchpoll was enjoying this. In a plainer world he did not have to bother with a fear of treading on social eggshells. But then Catchpoll had a reputation to keep up, a reputation for blunt speaking and sheer bloody-mindedness that had taken years to cultivate. Bradecote was excusing himself upon some pretext, ignoring the lady’s eyes pleading for him to remain. With a nod to Jocelyn of Shelsley, Bradecote extricated the three sheriff’s men from the hall.

Out in the courtyard he quizzed the serjeant upon the visitor.

‘Not a man as has come to the attention of the law, my lord, though he holds of de Beauchamp and so has been around on service. Surprised you have not come across him.’

Bradecote shook his head.

‘No. But then, I have not met all the sheriff’s vassals. Is he as dim as he looks? Surely he cannot be?’

‘Well, if he truly did not see the lady’s lack of, er, enthusiasm, he must be.’ Catchpoll sniffed. ‘But, you know, I think he is well aware, but putting a brave face on. As another vassal, and a kinsman, if the brother does not return, well he might be the one to inherit a tidy manor or two. He might think playing stupid has its advantages.’

Bradecote sighed.

‘And I have the joys of his conversation at dinner.’

Reginald, son of Robert, savoured the ale. He sat quietly, avoiding drawing any unnecessary attention to himself, sitting half in shadow. He appeared absorbed only in his cup, but he listened, and listened attentively. What was causing much discussion was the instruction to be on the lookout for the steel-grey horse with the white stockings. It was a fine animal, but clearly a liability. The reeve ambled in. He was in loquacious mood even before his jug of ale. Having had a nerve-wracking day, he was glad to unburden himself to a more appreciative audience than his wife. He found the pressure from the undersheriff a worry, and the intervention of de Lasson had been a welcome relief. Retelling what then went on between the two elevated his position, since he had grasped the gist of it, and made him feel that someone else might end up in worse trouble than himself.

‘My lord de Lasson will send his own men to guard his salt next time it is ready, you can be assured. He cannot afford to lose it if he has trade with the Welsh. They will look elsewhere soon enough if he fails them. And the de Malfleur men will be about their duties by Thursday to the priory at Leominster. Lucky the men with that cartload, and pity is for the poor souls, undefended upon the Worcester road.’

He rambled on about the Welsh in a way that would have angered any man of that lineage had one been present. The reeve was spared a beating, however. Reginald emptied his cup, wiped a hand across his mouth, and left, very content, and with a smile playing about the corners of his mouth.

Hugh Bradecote half filled his cup with wine. He needed a clear head for the morrow, and keeping up with the other man was out of the question. Jocelyn had drained three cups already and there was still meat upon the table. The conversation, if it could be called such, veered from slightly slurred monologues designed to show the lady how competent and great a lord Jocelyn of Shelsley was, in his own eyes at least, to effusive compliments upon his hostess’s person, which she obviously found embarrassing. Bradecote’s own efforts to keep the talk more general were ignored. He was desperately trying to find something to catch the man’s interest, and thus it was he let loose the information that Baldwin de Malfleur had lost a salt cart and was now offering to provide guards for others, at a price. The lady Christina froze, one hand halfway to her mouth with a morsel of bread. Bradecote instantly regretted his thoughtlessness. She paled, and the bread was crushed between her fingers into a shapeless, doughy lump.

‘If Baldwin de Malfleur has a hand in this, then you need look no further for your culprit, my lord.’ Her voice was a husky whisper. ‘Wickedness follows them, those of that name, like flies behind a dung cart.’

The slightly befuddled Shelsley looked owlishly at her.

‘But, my lady, this cannot be. De Malfleur lost a cart.’ He frowned, trying to concentrate upon his words. ‘A man does not steal … his own cart. You are letting your own female intu … intu … thinking, take control. After all, none knew Corbin would be upon that road, and there was no reason for de Malfleur to want him dead.’

Bradecote said nothing. For all the wine he had taken, Jocelyn’s words held true upon the latter points, though he would not wish to voice them out loud to the lady. She glowered at Jocelyn.

‘You know nothing, nothing, I tell you. You think because a man is a lord, because he went to the Holy Places, that he is some paragon? And he had no reason to want my lord dead? Well, the fact that he was married to me would be enough.’

‘I hardly think—’

‘Correct. You hardly think.’ She turned to Bradecote. ‘Baldwin would want to hurt me, twist the knife, aye, and heat it red-hot first. Arnulf taunted him with me, for spite, when Baldwin was young and more hot-headed. My husband was happy to have his brother lust after me, as long as he

thought Baldwin would not dare to do anything. Well, he drove him too far, but I would not be caught between the two. I told Arnulf when his little brother stole foul kisses, and Arnulf offered him Outremer or oblivion. So you see …’

‘What you say may be true, but …’

‘You doubt me?’

‘No, I did not mean that. But, my lady, there is absolutely no way in which your lord could have been killed because of who he was. It was simply where he was.’

‘If it was known from here? My lord had the journey planned some days beforehand.’

‘There have been two other attacks since, one upon de Malfleur’s wagon itself. No, truly, it cannot be that, though you never thought to tell me of the connection, did you?’

‘I … no. But it does not mean that what I say now is less valid.’

‘Not less valid, but there is no logical reason—’

‘So you think me just a weak-headed woman too?’

Bradecote sighed. This was so difficult to explain.

‘No, please believe me …’

‘Believe you, whilst you do not believe me?’

She was flushed, and her voice had an edge, a tinge of panic.

‘There, there, do not be distressed.’ Jocelyn smiled and his voice was patronising. ‘I shall protect you from this nasty Baldwin man if you are afraid of him.’

‘Afraid?’ Her lip curled in a sneer. ‘If he came here I would kill him.’

She took her eating knife and stabbed it into the tabletop. Her kinsman blinked.

‘But you are a woman. You need looking after.’ He leered and belched. There was nothing protective in his tone.

Christina’s complexion paled and the fire went from her. She looked suddenly vulnerable and distinctly uncomfortable. Bradecote frowned in surprise and then cursed himself for a fool. Of course she was worried. Her experience of men, intemperate men, would make her fearful of having the drunken Jocelyn in her hall while she slept. The mangled bread was discarded, and she picked listlessly at the remains of her meal. Jocelyn of Shelsley grew more voluble, giving his opinions upon a variety of subjects, driving Hugh Bradecote to the point where he could happily strangle the man with his bare hands just to get some peace. The hostess, by contrast, became monosyllabic. At the earliest opportunity, she rose to excuse herself, and Bradecote rose also, upon the pretence of going to open the door to the solar. As she passed him, he inclined his head and spoke quietly.

Blood Runs Thicker

Blood Runs Thicker Vale of Tears

Vale of Tears Faithful Unto Death

Faithful Unto Death Wolf at the Door

Wolf at the Door Hostage to Fortune

Hostage to Fortune Servant of Death

Servant of Death Marked to Die

Marked to Die Ordeal by Fire

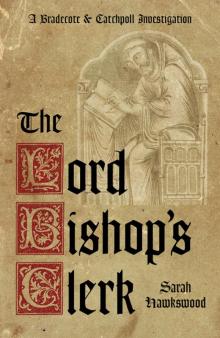

Ordeal by Fire The Lord Bishop's Clerk

The Lord Bishop's Clerk