- Home

- Sarah Hawkswood

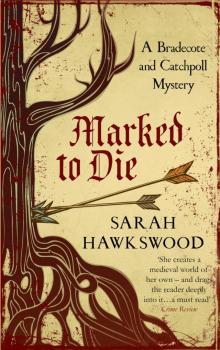

Marked to Die

Marked to Die Read online

Marked to Die

A Bradecote and Catchpoll Mystery

SARAH HAWKSWOOD

For H. J. B.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Author’s Note

About the Author

By Sarah Hawkswood

Copyright

Chapter One

The man leading the short train of heavily laden ponies wondered, idly, why it was that his bunions always ached more around the time of St Luke’s. It was an interesting thought. It was also his last.

The arrow struck true, and the packman died with no more than a grunting exhalation of breath. As deaths went, it was quick and easy, though unnecessary. In such troubled and violent times there were many such unnecessary deaths. Small comfort it would be to the widow, but it sat well with the Archer. Whilst technically a moving target, the pace was so slow that a lad of nine or ten, in the wavering stage of training at the butts, could have hit the man. Of course, it would have depended upon him being able to handle the draw weight of the bow, and he would not. Nor would it have been so clean a shot. The Archer would have been aggrieved at anything less. It was not so much a matter of pride as his own moral code, which he had learnt at the knee of his father, a hunter. The hunter stressed that killing was doing his job, and it was not wrong, but it had to be done right. An idle shot that wounded a beast was cruel, and also dangerous. The wounded animal was far more of a threat to the hunter. The Archer, plying his skill in the Holy Land for his lord, and after that man’s death, for any with the money to pay for his services, held that if it was true of dumb beasts then all the more so for humankind. He had no compunction about killing, no thought for the victim, nor qualms about gender or age, excepting infants, and, for a reason unknown to any but himself, the blind. But he made sure it was quick and accurate.

The second arrow took the man at the end of the train even as he ran forward, striking where neck met torso. He fell with barely more than a gurgle. Then the three heftily built accomplices came lumbering out of the bushes to lead the ponies away and conceal the bodies in the undergrowth. The ponies were jibbing and sidling, and one bucked and lashed out at the first thief, who swore as hoof contacted thigh. The Archer was not interested; he was not a thief. He would even have refuted the idea, had anyone thought to put it to him, that he stole lives. Man’s time was finite, and not guided by how he lived. Men died when their time was up. He was no more than an instrument of Fate.

He was turning away, about to unstring his bow, when he heard the hoof beats and the angry cry. A man, a man wielding a very serviceable sword in the manner of one trained in its use since youth, was bearing down upon the two men dragging away the corpse of the train leader. His blade sliced with an audible sound through the air, and one man crumpled with a curtailed scream. Without thinking, the Archer nocked an arrow and sent it to its mark. The mounted avenger toppled from his horse with a grunt, and the Archer turned away, unstrung his bow and disappeared among the foliage. He did not need to check whether the man was dead.

The lady in the solar was not initially concerned at the sound of a visitor, until a servant announced the Prior of Bordesley. Her lord was not due home before the morrow, for he had business in Wich and had then been due to visit the abbey of the White Monks, so she felt no stirring of alarm until one of that House was ushered before her. She rose, setting aside needle and linen with a polite, if watchful, smile of greeting that froze as she saw the man’s face. Only a bearer of bad news would wear a look like that. It was then an invisible hand grasped her viscera, clutching where the first inklings of life lay quiet.

‘Your visit is unexpected, Brother Prior.’ Her voice was low, unnaturally calm. ‘May I offer you hospitality?’

The Cistercian shook his head, and Christina FitzPayne noted the hands clenched together beneath the scapular of his habit.

‘I have news, my lady, unwelcome news, I am afraid. My lord FitzPayne did not arrive at Bordesley as he had sent word to Father Abbot he would, and … there was an incident upon the Salt Road from Wich to Feckenham the day before yesterday.’

‘An incident?’

Part of her wondered why this strange word dance was being performed. She already knew, with the inevitability of falling into an abyss, the end of it.

‘My daughter, there is no easy path for this. He was found dead about a mile from Wich, and two other men also, each with a fatal wound. The men were taking a train of salt towards Alcester. It is thought your lord came across the theft of the salt in progress and …’

‘My lord was cudgelled by some peasant thief? It is unbelievable.’

The denial was almost angry, as if she were trying to convince herself of it, and failing.

‘No, all three had fallen to arrows. The bodies were discovered yesterday and taken to Wich, where one of our brothers had been sent upon business of our House. He recognised the body of course, such a benefactor as the lord Corbin FitzPayne has been, and with the lord’s brother one of our fraternity. He requested that the body return with him to Bordesley, thinking he would be buried in our church, but, forgive him, he forgot you might wish him interred here.’

Christina’s head was spinning with so many jumbled thoughts. How would she contact Robert, Corbin’s other brother? Was he even still alive? All she knew was in whose train he rode towards the Holy Land to take service with the Templars. What must she do? She already carried Corbin’s child, perhaps his heir. Was it right to call the brother home? How would she see her lord received justice? Her own feelings did not exist beyond this freezing numbness within her.

‘My lady? Should you sit? You are most pale. It must be a shock indeed, but …’

‘I am sorry. No, no I need not sit.’ She tried to be logical. ‘Yes, he would be glad to lie within the confines of Bordesley and arrangements shall be made to provide for Masses for his soul, of course. Might I return with you to be present for the funeral? I would see him again, once, if that is possible.’ She paused. ‘Your journey has taken some hours; you should take a little food before we depart. Please, whilst I make preparations.’

She went to the door, calling for a servant, issuing instructions, working at practical things, avoiding the bottomless pit of darkness that threatened her. And then a thought occurred to her. She turned back to the brother.

‘What of my lord’s horse?’

‘Horse, and sword also, were gone.’

The monk did not think it fair to mention that the body had been found half stripped. He saw the frown upon the young woman’s face, the dark brows almost meeting.

‘The horse is distinctive, a dark grey, dark as dulled mail, but with a white star and two white stockings. My lord is … was … very proud of him. Where the horse is found, and the sword too, will lie the trail to the man whose life is now forfeit.’

She spoke softly, more to herself than to the monk, but the tone was icy cold and hard as iron, and the prior crossed himself.

A little over an hour later, garbed for travel, she led the way down the steps from the upper chamber, and it was then, as the cold October air hit her, that her body let her down and she

swayed, tried to steady herself and tumbled the last half-dozen steps. When she awoke, it was in pain and to the knowledge that there would be no posthumous heir to Corbin FitzPayne.

The Archer waited. He preferred to be in position early, and his honed senses told him of the arrival well before the man was in vision.

‘Stand still, and throw the money into the bushes before you.’

The man did so, with great care.

‘Now turn away.’

‘There is further work for you.’ The man spoke as he obeyed. ‘Half of the sum is in the scrip, half to be delivered afterwards.’

‘Fair enough. When and where?’

‘Two days hence, on the road through the Lickey Hills, just where the King’s land begins. There will be carts this time, two in number. Same plan as last time. Should be there a little after noontide for they are heading for Bordesley.’

‘And I do not have a particular man as my mark? You want no survivors,’ the Archer was matter of fact, ‘just as before?’

‘No survivors.’

‘I will be there, and the payment two days later, by the dead oak on the track to Inkberrow, just off the Salt Road.’

‘Yes, agreed.’

‘And you will be there?’ The Archer wanted that confirmed.

‘Oh yes, be assured I will.’

‘Then good day to you.’

The man would have echoed the farewell, but was suddenly aware that he was alone.

‘I am sorry, my lord. I am merely delivering the message.’

The messenger shuffled his feet, and wished himself elsewhere. William de Beauchamp, Sheriff of Worcestershire, growled like a bear, and looked apoplectic.

‘Upon the King’s highway, and against the Brothers of Bordesley, you say?’

‘And before that, my lord,’ the messenger delivered the additional bad news in a rush to get it over with, ‘there was the attack upon the pack train to the monks at Alcester, in which the lord Corbin FitzPayne of Cookhill was also struck down.’

‘What?’ If it were possible for the lord sheriff to turn an even darker hue, he did so now. ‘You should have told me this first.’

‘I … er …’ The messenger quailed.

Watching on the sidelines, Serjeant Catchpoll grimaced. He did not waste any sympathy. William de Beauchamp was not a man to appreciate dithering, and more fool the man who could not see it.

The sheriff glanced to the right and caught Catchpoll’s expression. The serjeant nodded. He knew where he would be heading.

‘You say “and before that”, worm.’ De Beauchamp fixed the messenger with a steely eye. ‘When was Corbin FitzPayne killed?’

‘It would be,’ the messenger shifted uncomfortably from one foot to the other, ‘six days ago, my lord, though there was no news of the second attack until late yesterday afternoon.’

‘You could come on foot from Wich to Worcester in under three hours, even if the place was suddenly lacking in horses!’ bellowed de Beauchamp. ‘Why was I not informed of FitzPayne’s death immediately?’

‘Earl Waleran’s reeve did send a message to the earl’s man, in his lord’s absence abroad. Perhaps the reeve thought he might …’ The messenger’s voice trailed off.

William de Beauchamp ground his teeth, audibly. Robert de Bernay was away from Worcester, but would no doubt find out soon enough and be demanding to know what the sheriff had done about it all.

‘And did not FitzPayne’s lady think I might be interested?’

‘I believe the lady was stricken, when she heard the news, and was unable to even attend the burial at Bordesley.’

‘Heaven protect me from die-away women!’ The sheriff halted, struck by a question. ‘Why Bordesley?’

‘His brother is a monk there, my lord, and he is … was, a benefactor. Indeed, I was told he was on his way to visit the abbot when he was murdered.’

It had a logic to it. The sheriff moved on.

‘Are there indications as to the culprits?’

‘None, my lord Sheriff.’

‘Well, I shall straightaway …’ de Beauchamp faltered as a clerk whispered nervously in his ear. The sheriff’s frown became a black scowl. There was a perceptible pause, ‘… send for my deputy to investigate this, since I am called away upon the Empress’s business. Catchpoll, go to Bradecote directly and take my undersheriff with you to Wich. And you can take that flame top with you.’

Catchpoll narrowly avoided grinning at the sheriff’s description of young Walkelin, his protégé. He also wondered at the warmth of reception he might receive from Hugh Bradecote, the undersheriff. Not that it mattered much.

Hugh Bradecote had a measure of peace, though when his son’s infant wailing seemed to fill his hall it was not of the auditory variety. At times, the crying was jarring upon the nerves, and yet he savoured it, giving thanks for the lusty cries that demanded attention. The womenfolk all greeted it with approbation so he knew he should not worry, and after the first heart-stopping panics, he learnt to smile at it. That was his son, Gilbert Bradecote. With a twinge he remembered the babe was Ela’s son too, all that remained of her. It was odd, he thought, how fast she had faded from his thoughts, not his memory, but his everyday life. Even alone in their bed he did not think of her. He felt a mixture of relief and guilt, and, in the little church, prayed for her soul most devoutly.

The manor had settled remarkably quickly back into a rhythm, perhaps an easier one without a lady who tended to remember everything at the last minute and in a wild rush. Hugh Bradecote had returned from Worcester for the Michaelmas feast, if not happy, then at least not in the grey nothingness that had at first flooded him and left him barely functioning. He threw himself into the busy autumn tasks upon a manor in preparation for the winter to come, and wanted to achieve as much as possible before he had to return to Worcester upon his feudal duty at All Souls. The arrival in his bailey of Sergeant Catchpoll, with Walkelin at his side upon possibly the most moth-eaten horse he had ever beheld, more than a fortnight before he should depart, tossed that hope into the fire of lost aspirations. And yet he felt glad to see the pair of them.

Catchpoll’s mount, as if able to mimic its rider’s take-it-or-leave-it attitude, ambled in with head low and on a loose rein. Walkelin’s horse arrived at a pace as mixed as its coat, which was in the midst of an early-winter growth, and in shaggy patches. Catchpoll nodded to the undersheriff, and dismounted, swinging his leg over the horse’s neck with an ease at odds with his years, unless you heard the muttered oath beneath his breath. Hugh Bradecote did, and pretended not to notice the slight giving of the knees as the serjeant reached the ground.

‘I take it you are not being social, Serjeant Catchpoll.’ Bradecote smiled wryly and nodded an acknowledgement to Walkelin.

‘Not as such, my lord. I leaves social calls to mendicant friars and gossipy women. Think of this as more a shrieval request you just can’t refuse.’

The smile was met by the death’s head grin that Bradecote had come to know well.

‘That is how I think of all requests from my overlord.’

‘Wise, my lord, very wise.’

Walkelin, understanding now that this must be by way of a near ritual re-establishment of the relationship, silently dismounted and gave his moth-eaten horse a look of loathing. It stared back at him, and he was convinced the feeling was mutual. He made a glancing assessment as he looked round the bailey. Serjeant Catchpoll had been training him to do this over the last weeks, and might well ask him where the pitchfork was leaning, or what he could deduce about the manor from the general environment. He would say, even if he did not know the undersheriff, that this was a manor run by an attentive steward whose lord liked everything orderly and no doubt had every barrel of apples and bushel of grain accounted for in the stores. The pitchfork was beside the small door to the right of the stable.

The heavens, which had been threatening to open for the full five miles of their journey, now gave up any attempt at restraint,

and large, heavy drops spattered on the ground and seemed to go straight through the man-at-arms’ cloak. Bradecote ushered his visitors up the steps and into his hall. The warm woodsmoke assailed the nostrils from the central hearth, and Catchpoll went to spread cold, and slightly stiff, hands before the heat, even though the smoke tendrils caught in his throat and made him cough.

From the solar came the sounds of an infant making its presence known.

‘My son does not ask politely, he demands,’ Hugh Bradecote grinned, and could not keep the pride out of his voice. Catchpoll would not begrudge it to him.

‘I hope you intend to teach him to demand in good plain English, my lord.’ Catchpoll’s tone was respectful but with a teasing edge. ‘He’ll get further in life if he has the English too, like yourself.’

‘Oh you can be sure he will, since wet nurse and nursemaid understand no other. Most likely it will be a trial teaching him anything else.’

The yelling reached a new pitch of intensity.

‘He certainly sounds as if he is thriving, anyhow, and has learnt not to take no for an answer, in any tongue.’ Catchpoll sounded approving.

‘The nurse keeps telling me how big he is, and I am trusting her judgement.’ Bradecote shook his head in mild wonderment. ‘I never really studied infants before.’

‘It’s suddenly different when the mite’s your own, my lord. I speak as one who had five and now,’ Catchpoll paused for mental calculation, ‘I have eight grandchildren dotted about. At least it was eight last time I looked.’

He omitted to say that the numbers did not always increase. Why rub in what every man knew: the early years of life were precarious. He had been fortunate to only lose one son in infancy and one daughter was gone now in childbed, but Catchpoll knew he was a blessed man, and gave heartfelt thanks for it.

Bradecote focussed his mind upon the matter to hand.

‘So, what has the lord Sheriff of Worcestershire sent his law hounds trailing after this time, Catchpoll, just when I was settling back into my own life?’ He wished the call had not come at this juncture.

Blood Runs Thicker

Blood Runs Thicker Vale of Tears

Vale of Tears Faithful Unto Death

Faithful Unto Death Wolf at the Door

Wolf at the Door Hostage to Fortune

Hostage to Fortune Servant of Death

Servant of Death Marked to Die

Marked to Die Ordeal by Fire

Ordeal by Fire The Lord Bishop's Clerk

The Lord Bishop's Clerk