- Home

- Sarah Hawkswood

Ordeal by Fire Page 7

Ordeal by Fire Read online

Page 7

His wife, misreading his silence for old memories, patted his hand and rose with a sniff to ladle out his dinner with her former anger forgotten.

Bradecote lay upon his bed with his mind busy, but free from the grey and formless misery that had beset him. The seemingly insoluble mystery of the case gave his brain something new upon which to focus, and in doing so gave him ease. He slept, and if it was a little late then at least the slumber was not haunted. When he awoke to the new day he was aware that the lassitude that had enfolded him had been cast aside. He might still bear dark rings around the eyes but his brain was working at normal speed, unfettered at last. It was therefore an undersheriff in positive mood who greeted Catchpoll after a brief breaking of fast.

The serjeant was, in contrast, more than usually morose, and acknowledged his superior with the briefest of nods and a grunt, which Bradecote might, if he had the inclination, interpret as greeting. Bradecote thought him preoccupied, and attributed it to his plan for the morning’s investigation, so made no comment. After a brief exchange, the pair split up; Bradecote to Simeon the Jew and Catchpoll to undisclosed addresses within the town.

Simeon’s house was a good-sized property at the end of Cokenstrete away from the Severn. It was clearly kept in good order but there was nothing to show that the occupant was wealthier than any other in the street, nor different in any way. Only when Bradecote stood at the doorway did he notice the small gouged hollow in one of the thick upright beams, with a thin roll of vellum nestling within it. He frowned, wondering what it might be, and the look of perplexity was still present when a serving man opened the door to him. The man was polite but wary, casting glances both up and down the street before asking the visitor’s business. He bid Bradecote enter, and another surprise awaited the undersheriff. There was a heavy carved screen across much of the room, thereby creating a small area at the front of the hall where clients might wait until Simeon chose to receive them. Bradecote appreciated the ploy. It put clients at a disadvantage if Simeon so wished. On this occasion the servant led Bradecote straight round and into the main part of the hall, which was lit by the pale light from the upper windows at the front of the hall, above the height of the screen, and by several large candles on tall stands. The sheriff’s officer was conscious that the house smelt different to any he had been inside: sweeter, but not like honey; rich and slightly exotic. Well, the man was a merchant with goods coming from distant lands, so perhaps he kept some of the most valuable in his home.

The master of the house was seated at a table towards the back of the hall, with a small boy upon his lap reciting in a language that Bradecote did not know. The child’s face was pinched with concentration, and he did not register the arrival of the stranger. The servant did not announce Bradecote, but stood still and waited. The child rushed the last phrases of whatever he had committed to memory and then looked up to his father’s face seeking approbation, only relaxing and grinning back when his father smiled and nodded at him. The movement broke the spell, and the servant announced the undersheriff.

The father looked up, paternal pleasure replaced by wariness. He patted the little boy’s cheek and dismissed him with some comment that set the child laughing as he was put down and half skipped to a chamber at the rear of the hall, where a woman’s voice could be heard from beyond the partially closed door.

Simeon rose unhurriedly, and greeted Bradecote with formal courtesy. The undersheriff felt guiltily surprised, for the man spoke with only the suggestion of an accent. Without reason, Bradecote had expected someone distinctly foreign. In appearance, Simeon would certainly stand out among the citizenry, having a warm tone to his skin that Worcestershire natives might only get after a summer of labour in the fields, but without the weathering. More striking still was the blackness of his hair and the full, well-kept, glossy beard, unlike the thin, jaw-edging variety that was worn by most men who chose not to be clean-shaven. He had deep bay-brown eyes; eyes that assessed the undersheriff swiftly and accurately. Simeon depended upon his judgement of his fellow man, both in his trading and for his own security. He sensed Bradecote’s uncertainty but could see that it did not spring from diffidence. The tall, dark man before him exuded competence and probity; a man whose word could be trusted. Such decisions on character came easily to the merchant. He smiled a little more broadly, although the eyes remained watchful, and invited Bradecote to be seated with a broad sweep of his hand.

‘Forgive me, my lord. I try to make a few minutes each day to hear my son’s learning, and if the hour is late he makes mistakes and is frustrated. He is a good boy and tries hard. You have sons?’ It was a conscious manoeuvre to link himself with his visitor.

Bradecote caught his breath as he was about to answer in the negative, and coloured.

‘Yes. I am now the father of a son, but he is no more than a swaddled babe.’ There was a suggestion of pride in his voice, but Simeon had caught the grey shadow that had passed across his face and made a wise guess.

‘A son is a man’s comfort. May he grow strong and be always a credit to you.’ He spoke as if it were a formal benediction, and looked Bradecote straight in the eye. The moment was all that was needed to convey understanding and sympathy, and then it passed and Simeon assumed a more formal tone. ‘And how may I be of service to you, my lord Undersheriff? It is official business, I take it.’ The use of the title and Bradecote’s demeanour had immediately dispelled any idea that this was a man seeking the services of a usurer.

Bradecote cleared his throat. ‘Indeed it is, Master Simeon. There have been several fires in the town in recent weeks, probably not mischance. I am seeking to find out if this is so, and who it is who puts the town at risk. I am asking questions among the merchants and those linked to the locations of the fires.’ He spoke carefully and without emphasis.

‘I see.’ Simeon’s full lips pursed. ‘The fires, as I have heard, were at the premises of Master Ash the silversmith and in Corviserstrete. I have made purchases for my wife at the silversmith, but I have no connection with Corviserstrete. I trade, my lord, but I own no property beyond my own house and wharfage. I assume, therefore, that I have been pointed out to you merely because I am “Simeon the Jew”. It is always so much easier to blame the outsider.’ There was a weary understanding in his voice.

‘That is true, but I do not seek someone to blame, only the truth, and I would be neglecting my duty if I did not speak to all those who were brought to my attention,’ Bradecote paused for an instant, ‘even if I questioned the motives of the informant.’

The two men said nothing, each gauging the other. Then Simeon nodded. ‘That is fair, my lord. I will give you any answers that I can, but I cannot see that it will aid you, for I fear I have nothing pertinent to say.’

‘Then I will start with the obvious. Have you ever been in dispute with Reginald Ash, over his work, or had financial dealings with him?’

‘No, my lord. He is accounted a prudent and honest member of his craft, I know.’ He smiled ruefully. ‘It is in my best interests to know about the other tradesmen in Worcester, so that I can judge whether they would be good “clients” if ever they did come to borrow money. But in truth, much of my livelihood still comes from “honest trade”, however difficult it is for us in these times. I have goods come up the Severn from Bristow, where I come from, or rather, where I was born; spices from the Mediterranean; citrus fruits and other rare commodities that other merchants do not often carry. My grandsire came to England from Portugal, and I have good family ties there. The family works together. So far none has tried to prevent us continuing in this trade and of course we “enjoy” royal protection, as long as we pay our taxes for the privilege and accede to requests for royal loans. I sometimes wonder how this strife would be paid for without us to pay the soldiery.’

He could see that he held Bradecote’s interest. The information might have nothing to do with fire-setting, but it was useful background if the undersheriff was to work in the town in fu

ture.

‘We have a false reputation, we Jews. Because our faith, though far older than yours, is alien to you, because our language is foreign and because we do things in a different way, we are regarded as untrustworthy, even dangerous. I have seen mothers shield their children as I passed as if I carried foul plague, as if I were some fierce monster.’ He opened his arms and shrugged. ‘Yet I am merely a man. We lend money because in many places that is all that is left for us to do. One day perhaps, I will have to exist upon it if my trading is forbidden, and I will make the best deal that I can, for the sake of my business and my family. It does not make me greedy.

‘I have even loaned money, once, at no interest at all, but I would be obliged if you did not make that common knowledge.’ Simeon’s eyes twinkled. ‘There was a good woman, many years ago now, only a few years after I came here, whose husband died in debt. He was persuaded into an enterprise by others who made sure that any risk lay with him.’ Simeon shook his head at the man’s foolishness. ‘The widow was pious and honest, and once did my Rebekah, my first wife, a kindness. She knew who Rebekah was, but did not hold back from helping her. When the husband died she lost everything to the creditors and was reduced to taking menial work to survive. She wanted to spare her son the poverty and the shame and sought to put him into the cloister, but she did not even have the money to provide the “gift” that would accompany his application. I provided the money …’ He laughed without mirth. ‘A Son of Abraham funding a Benedictine. How strange is that? But that woman paid back every silver penny within a year, though I am sure she often went hungry. She married again after that, but I do not know what became of her thereafter. She deserved better fortune.’ He was half talking to himself by now, but roused himself to gaze at Bradecote. ‘Perhaps it was a godly deed, perhaps mere soft-heartedness. I do not care to judge, but can you imagine a “Christian” man like Robert Mercet, doing the same?’

Bradecote was actually relieved to hear the merchant’s name. It brought the conversation back to the current problem without him having to labour the point.

‘No, having met the man I would not say that was even possible. I take it that you and he do not engage in pleasantries.’

Simeon gave a crack of genuine laughter. ‘“Engage in pleasantries”, no indeed. He would slit my throat as soon as look at me, and I … well let us say uncharitable thoughts have been known to pass through my head. It was he who brought my name to your attention, wasn’t it.’ It was a statement not a question. ‘No need to answer. He would love to see my downfall, and pick the rich scraps from my business.’

‘And is the feeling mutual?’ The question was almost casually put, but Simeon was nobody’s fool.

‘Would I ruin him? Of course, my lord, of course, but only by good business means. You are going to say he has holdings where the fires occurred? Well, my lord, I would see him sink in debt as deep as the Severn and laugh, but I would not risk honest business or innocent lives. You must look elsewhere for your fire-raiser.’

‘Can you think of anyone else with feelings like yours, but less compunction?’

‘I would be surprised if there were more than a handful of townsfolk, outside those who work for him, and perhaps not even them, who would not call a holiday at his fall, but I could not point a finger at anyone prepared to do violence, except upon his person directly, that is.’ Simeon had relaxed. Bradecote’s questions had not been those of a man keen to find a scapegoat. He was, as he had claimed, merely a seeker of truth.

The sound of a baby’s insistent cry came from the rear chamber, followed by a woman’s crooning. Bradecote winced and Simeon, conscious of not having offered hospitality, knew that the undersheriff would not choose to linger. He rose.

‘If there are no more questions, my lord, then I would be about my business. I have a boat due in this morning. I apologise for not having offered you refreshment.’ He bowed.

‘It is no matter, Master Simeon. May I walk with you to the riverside?’

‘Shrieval approval, my lord?’

‘Let us just say that I would not want others to be incited to take the law into their own hands.’

‘Then I thank you. Your company would be an honour.’ He bowed again, and called for his cloak.

The two of them made their way unhurriedly to the riverside wharves, the tall undersheriff and the Jewish merchant, and Bradecote knew that eyes followed them and made note. It was a good thing. He could not see Simeon as a fire-raiser, though facts might yet emerge to the contrary, but he did not want Mercet to be able to achieve his ends by rousing the townsfolk against Simeon simply because he made an easy target. The warehouse was busy, and assailed the nose with a myriad of exotic smells. On the riverside the doors were open, and men were unloading sacks and bundles from a sailing vessel. Simeon stopped a man with a small box on his shoulder and opened the lid. Inside, nestled in straw, was a handful of bright-yellow fruit. He took one, squeezing it gently and then holding it to his nose. He inhaled and smiled.

‘I did not offer you refreshment in my home, for which lack of hospitality I ask forgiveness, but perhaps I may atone for it here. It would not be corruption of the sheriff’s office if I were to offer you this?’

Bradecote smiled. ‘No, I think not. But,’ he looked at the strange thing, ‘what is it?’

‘A fruit. A laymun. It grows on trees in Spain and Portugal, but long before that in Lebanon and in groves even about Jerusalem. You will not have seen one.’

Bradecote shook his head.

‘This laymun, it is very sharp to the taste but good in cooking. I will please my wife very much by presenting her with one as a gift.’ He proffered it to Bradecote, who rubbed the skin gently and smelt it. ‘The flesh inside is sharp, as I said, and the “pépins”,’ he used the French word, ‘which are pale, are towards the centre. You could not plant the seeds to make it grow here, though. England is too cold a country. Sometimes in the winters, I agree with the laymun.’ He smiled. ‘Take it back with you to your manor and have the cook take off the thin outer skin and put it in butter to flavour it, and the juice mix with honey to sweeten it, and warmed English wine. I would say you will be one of the only men in the shire to have come across it, though those who have been to the Levant will know of them. I have purchased a small box. They will fetch an extremely high price with the lord Bishop of Worcester, and the lord sheriff perhaps, higher than nearly all of my spices.’ Simeon smiled in anticipation.

Bradecote thanked the merchant and left him to his business. The interview had been interesting, but he could not see that it had advanced his hunt for the fire-setter. He wondered if Catchpoll had gone back to see Reginald Ash, since Martin Woodman the carpenter would not yet be returned, and so made his way to the silversmith’s. The craftsman was at work, but had not seen Serjeant Catchpoll that morning. Bradecote decided to ask the relevant questions himself, but they availed him little. Ash had only met the carpenter on a few occasions, the last being some six months previously, when Woodman had been making a casket in which a fine goblet was to lie before being presented to a visiting prelate. In addition, the premises were the property of Master Ash himself, who had inherited them from the master silversmith whose apprentice and journeyman he had been.

‘’Tis one of the reasons I am content to make Edwin my partner. In the fullness of time, and may that be a long time, mark you, he will take the business as I did before him. It seems very fitting to me, my lord. Sort of natural. He’s a good fellow is Edwin. I could not have had a son I would be more proud of, all in all. It wasn’t that way with my master; not close we weren’t, but Master Long recognised a good craftsman.’ Ash shook his head at his memories. ‘Gave me a few rare beatings in my youth for my errors he did, and he was a warm one at business, but he left me a fine inheritance here. So may God have mercy upon his soul, I say.’

Chapter Seven

The sun was now high and the shadows short. It had been a most frustrating forenoon, and Bradecote h

oped that Catchpoll had had more success, even if it meant the serjeant gloating upon it. When he came up with him before the castle gate, however, there was no look of triumph on Catchpoll’s weathered face. If anything, he looked even more glum than earlier.

‘I had thought to find you with Reginald Ash, Catchpoll. Did some more likely quarry draw your attention?’

‘Not quarry, merely checking details.’

‘Thorough checking it must have been then, if you did not get as far as Master Ash.’ There was an edge to his tone.

Bradecote’s eyes narrowed a fraction, for he thought that Catchpoll looked uncomfortable, and he had not seen that before in his dealings with him. It occurred to the undersheriff that an investigation outside of the usual criminal suspects might involve ferreting closer to home than was the norm, and perhaps even such an old hand as Catchpoll might dislike it. Part of him would have liked to put Catchpoll on the spot, but at heart he knew it would be unfair. If anything relevant turned up, he trusted Serjeant Catchpoll to bring it to his attention at once. If he could not trust him to do that, then their working relationship would be worthless. The serjeant said nothing, so he continued.

‘Well then, I have to say that other than having been making the very interesting acquaintance of Simeon the Jew, and been given this,’ he held up the fruit, ‘which is, it seems, called a laymun, I do not think I have made any advance. I went to Reginald Ash, who apparently took over the business from his old master, a craftsman called Long. There seemed nothing that would help us. Any luck your side?’ The question was casually put, but carefully so.

Blood Runs Thicker

Blood Runs Thicker Vale of Tears

Vale of Tears Faithful Unto Death

Faithful Unto Death Wolf at the Door

Wolf at the Door Hostage to Fortune

Hostage to Fortune Servant of Death

Servant of Death Marked to Die

Marked to Die Ordeal by Fire

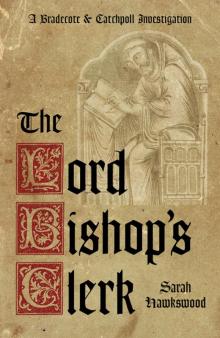

Ordeal by Fire The Lord Bishop's Clerk

The Lord Bishop's Clerk