- Home

- Sarah Hawkswood

Marked to Die Page 4

Marked to Die Read online

Page 4

The genuine disgust upon Hugh Bradeote’s face touched her. Most men would merely not approve. It was wasteful, unkind, and showed a lack of control to use a wife, in name but of child’s years, for the bedchamber. There were women enough elsewhere until she was a woman grown at fourteen or fifteen and could bear heirs.

‘I was not fourteen when the first came, but it came early, far too early, and never drew breath. He blamed me.’ She laughed without any humour. ‘So he beat me, lashed me like a cur, so the white scars linger on my back still as a remembrance of my failing, and dragged me from my sickbed to do so. In the end it felt a black sin to bring forth his sons. The daughter, ah she was different, and he ignored her even until the day I buried her, when she was four, but his sons …’ She shook her head. ‘Mother’s love children, be they comely or ugly, wilful or sweet-tempered, but I had that driven from me. He did not want me involved with “his” sons; I carried them in my belly, nursed them at my breast, but thereafter they were his to mould, and he made them in his own image, without care of any creature, man nor beast, encouraged cruelty, taught them to despise me. But oh, he was proud of them. Have you sons, my lord?’

‘I have one, a babe still.’

‘And is your lady proud of him?’

‘My wife died giving him to me,’ Hugh Bradecote spoke softly, ‘but I will raise him so she would be proud, yes.’

It was the acknowledgement of an unconscious thought. He knew he could tell Gilbert little of his mother, since in so many ways he had never understood her, but she had been gentle and dutiful and loving, and had been proud, even at the time of dying, that she had borne a son.

Christina FitzPayne bit her lip.

‘I am sorry.’

‘God’s will.’

‘Yes. Arnulf’s sons died. I believe that was God’s will also, but to protect this earth from Malfleur’s evil blood. I should have mourned, but I was just relieved. One was killed in a fall, setting his poor pony at a ditch it could not cross, and urged on by his father; the other died of a sudden fever when in his first year as a squire to de Mandeville in the east. When Arnulf died of the flux before Lincoln, I was free.’ Her eyes glittered. ‘He suffered, so I heard, and I was glad. He did not even live to die with what men call “glory” in the battle, just in his own filth in some tent among the Empress’s followers.’ She saw Bradecote’s eyes widen slightly. ‘You are shocked, yes, that I can be so unforgiving, so unwomanly. Just know that whatever bad things you heard of Arnulf de Malfleur was only the part of it. The blood is tainted with evil. Baldwin, Arnulf’s brother, has no child still, so, God willing,’ she crossed herself, ‘the world will be spared more of that line.’

‘So you were married how long to Malfleur?’

‘Nigh on fourteen years. Half my life and yet three lifetimes. Corbin, well, Corbin was safe and kind, in his way. His demands were not excessive and after a happy marriage, which was yet without a child, he was so delighted to find he had the chance at last. He was going to tell his youngest brother Eustace, who took the cowl years ago and is at Bordesley.’ Her face clouded. ‘And in the shock of his loss I slipped and failed him, robbing him of his posterity. Perhaps it was my penance for not loving the other sons I bore.’

Bradecote watched her, the pale hands, with their long, delicate fingers, entwined so tightly the knuckles showed white, the eyes dark with misery. This was not a woman who had betrayed her husband with a lover and arranged his death. Then he realised that she in turn was watching him, assessing him. Her eyes widened, not in horror but in anger as she read his thoughts. She caught her breath, stood swiftly, holding the edge of the table for support as she swayed with the blood rush, and swung her hand hard so that his cheek stung with the raised weal. It was totally unexpected, undefended.

‘How dare you? You thought that I … that …’ Words failed her.

The pale cheeks flew angry red patches, and she turned to go to the solar, but his hand went out and gripped her wrist. She looked down upon it as if on a defilement.

‘Let me go, my lord. You are one with all the rest.’

Was there disappointment in her voice? His cheek throbbed. He was angry, but angry with himself.

‘I am sorry. Really, I am. The thought had to be entertained. I did not know anything of you, of your past, of what manner of woman you are. I am sorry, lady, for I did you injustice.’

She did not look at him, but at the floor. All fight was suddenly gone from her, and her shoulders slumped.

‘Let me go,’ she repeated, but softly, and he freed her instantly. She walked slowly to the solar door, and then turned, raising her head high. There was a catch in her voice when she spoke, but she spoke firmly. ‘Injustice, yes, but I will have justice for Corbin FitzPayne, and for the son I could have loved.’

Hugh Bradecote swore under his breath as the door closed, and when he settled to rest for the night, his dreams were haunted by the keening of a woman for a lost child.

He woke with the dawn, not refreshed, nor in the best of tempers, and did not know whether to be cheered or not by the similar look of thwarted sleep upon Catchpoll’s grizzled features, when he met him in the courtyard. Walkelin, however, appeared fresh and cheery, and full of news. His superiors gazed at him with undisguised revulsion.

‘By the Rood, if you look that cheerful of a morning, I will have to throw you in the midden,’ grumbled Catchpoll, morosely.

‘It is a fine day, and the cook has a way with fresh bread that many a Worcester baker would envy.’

‘You know,’ remarked Catchpoll conversationally, ‘most men are ruled by their bodies. It gives the law a lot of work. But if they were ruled by their belly, as Walkelin is, well the rate of killings would drop but the thefts of oatcakes would treble.’

Walkelin, unabashed, grinned, and permitted himself half a glance at a comely wench bending forward in an appealing manner as she sat down upon a stool and began to milk a goat.

‘I agree with Serjeant Catchpoll, Walkelin.’ Bradecote ran a hand through his tousled hair. ‘The sight of your grinning visage is enough to turn a man’s stomach before he breaks his fast.’

‘But I have already broken my—’ Walkelin halted at a warning look from Catchpoll, and attempted to school his open features into a more sober expression. ‘Er, I got talking with a couple of men-at-arms over a cup of ale last night, my lord. I don’t think the idea that the lady FitzPayne might have paid to have her lord done away with will work.’

Bradecote did not say that he was already convinced of that.

‘And why is that, Walkelin?’

‘He was married before and had no children, it is true, but his lady could not hold a babe it seems. She lost them early. So he had no reason to assume a child was not his. And besides, they were but married less than two years, and were said to be content, no shouting, no throwing of things.’

‘Shouting and throwing things does not mean they were not happy,’ Catchpoll scowled, thinking of some of the times ladles had been lobbed at his head when he arrived home late, to a dried-up pottage. ‘Some couples do, some don’t. Silence can be worse. Nonetheless, I have reached the same conclusion as Walkelin, my lord. She did not want him dead. The tirewoman says how she was anxious every month, hoping for a sign, and when she was sure she was delighted and told her lord straightaway. He could scarce contain himself, but was anxious for her health and would barely let her set foot out of doors for the last week or two.’

The undersheriff nodded, and agreed that everything pointed to the widow being innocent of any involvement in the deaths, without elaborating upon his own findings.

‘Not that this is grounds for self-congratulation, of course,’ he sighed. ‘We have eliminated one person but have no idea how many others might be suspect. And although she was someone we had to ensure was not involved, she was not the likeliest. It would have meant her having an unknown lover and them being content to see four other men killed just to cover their tracks. It was not im

possible but …’

‘Trouble is,’ Catchpoll sighed, scratching his stubbled chin, ‘there is nothing so far to send us in the right direction. We need to find out why, if Corbin FitzPayne was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, two loads of salt have been stolen and the carriers murdered. I have seen lots of thievery over the years, and most thieves are happy to hit the victim over the head and be away with the goods. Sometimes they live, and sometimes they die, and the thief cares neither one way or the other. In this case these men were clearly not meant to survive, and that worries me. It isn’t normal crime, if you understand me.’

Walkelin, his flame-coloured eyebrows drawn now in a frown, sniffed and wiped his nose on his sleeve. ‘What would you do with two loads of salt that were heading for those who owned it? I mean, is someone keeping it to sell? If they are trying to raise the price of salt, well, they would have to take a lot more packhorse loads, and they cannot turn up to the monks at Bordesley and Alcester in a week or two and offer to sell them salt at a higher price.’

‘It might make our task easier.’ Bradecote smiled. ‘Is it some grudge against … I was going to say the Benedictines, but the abbey at Bordesley is a daughter house of the White Monks at Garendon. In that case, is it a grudge against religious houses in general?’

‘If you wanted to do something, more like you would burn down their granges, put dead livestock upstream of their water courses, or poison their fishponds, my lord.’ Catchpoll spoke meditatively.

‘You have a nasty turn of mind, Catchpoll.’

‘Thank you, my lord. It comes in handy.’ The serjeant gave a modest smile, which was not a look he employed regularly.

‘I think,’ and the undersheriff sounded prepared to entertain any better ideas, ‘we should go to the monks at Alcester and then on to Bordesley anyway, just in case they have received threats or …’

‘… kept the arrow from Corbin FitzPayne, my lord, since they would not bury him with it still sticking out of the corpse, and then we would have two.’ Walkelin sounded quite excited at the prospect, but Bradecote winced at his loud exuberance, and Catchpoll gave him a hard stare.

‘I think perhaps less joy in the dead man’s own bailey might be in order, Walkelin.’

‘Er, yes, my lord. Sorry, my lord.’

Thus chastened, Walkelin coloured, even more so at the sound of a small giggle from the goat-milker. He took a sidelong glance at her and caught a blushing smile, which darkened the shade of his cheek further.

‘And keep your eyes off wenches,’ murmured Catchpoll through the side of his thin mouth. ‘Gives a young man ideas, a buxom maid like that, and you’ve not time for ideas that aren’t to do with these killings.’

‘No, Serjeant,’ but the eyes did stray once more and got a wink.

Bradecote stood, with folded arms and a sardonic smile.

‘So sorry to disrupt your love life, Walkelin, but perhaps you might just go and arrange for the horses to be prepared. I will make our temporary goodbyes to the lady and then we can be away.’

He turned, and was halfway up the steps when lady FitzPayne appeared at the top, her veil being plucked by the gusts of autumnal wind and a dark, heavy cloak wrapped around her. If anything it made her more wraithlike than the day before. The shadows beneath her eyes seemed deeper than ever, and her face was as emotionless as one laid out for shrouding. He stopped, looking up at her, and with a stab of regret that she could not face him with even the most formal of smiles.

‘I was coming to tell you, my lady, that we are away to Alcester and then on to Bordesley. We may return here in a day or so, dependent upon what we discover.’

She looked at him coldly, and acknowledged his words with a regal inclination of the head.

‘Then I wish you a safe journey, my lord.’

Her voice was flat, dead. She might as well have been ordering a goose for dinner. It should not matter to him, and yet it did. Last night she had been all passion, wounded passion but alive. Now she stood there like an empty husk of grain, and as likely to be blown away in the wind. He made her an awkward obeisance from his halfway position, and retraced his steps, aware the exchange was under scrutiny.

Catchpoll’s eyes narrowed to slits. Body language alone told him much. So the lady had taken against his superior, had she? He wondered why, for the undersheriff was not generally a clumsy man in word or action. He also wondered when any mention of this falling-out might be passed on, if at all, but wisely kept his mouth shut.

Walkelin appeared, leading their horses, and the three men mounted up and trotted out of the courtyard, watched by several of those present. Bradecote did not glance back, and chided himself for a fool for having wanted to do so.

As soon as they had gone, the girl who had been milking the goat handed her pail to a child, wiped her palms on her skirts and, bobbing a curtsey at the base of the steps, approached her mistress.

‘Well?’

‘They seem to have no idea as to who did the killings, my lady, but they do not think the lord FitzPayne was the object of it, more that he was an accidental murder, if you see what I mean. But they do have an arrow, and hope they might find another.’

‘They would take such a thing with them, but when they return it would be well if we relieved them of that burden. Good girl, tell Godwin to fetch you an apple from the storerooms.’

The maid thanked her, and the lady FitzPayne returned to the hall, one hand clamped against the echo of discomfort within her, the other twisting the end of the heavy, dark plait that coiled over her shoulder and peeped from beneath her headdress.

Chapter Four

The three riders chose to head north to the Salt Road and then turn east to Alcester rather than ride across country, for it was but some four miles and the Salt Road was quick and easy. They arrived at the abbey shortly after the brothers had finished Chapter. It was a comparatively new foundation, only a few years old, and the claustral buildings were still largely of wooden construction, although the abbey church now boasted a stone chancel and transepts, with signs that work would advance again come the spring.

Abbot Robert recognised Serjeant Catchpoll. He had been a monk and obedientary at Worcester before the foundation of the abbey a few years previously, and Catchpoll’s was a face that, once seen, was hard to forget. He greeted them graciously and bade them ask all the questions they wished in the modest abbot’s lodging.

‘I fear that we can assist you little, if at all, in the solving of this wicked crime, my lord. The salt was ours, from our salt house in Wich. All that we knew was that a rider came from there to tell us it had been stolen and two packmen murdered, and also my lord FitzPayne of Cookhill, a good man and generous also. We can tell you nothing but the results of the deed.’

‘You did not know the date of the salt leaving Wich, then?’

Serjeant Catchpoll was casting about like a hound for any useful scent.

‘Oh no, Serjeant. We knew it would be coming shortly but the date of its arrival was not required, though,’ Abbot Robert sighed, ‘we might be short for the salting of our winter meats and fish. But our brothers in Worcester have said that they should be able to send some from their salt houses, for they have more. It is time that is our problem, not the quantity, in the longer term.’

‘This must sound a strange question, Father, but has anyone cause for dispute with you?’ Bradecote posed the obvious question.

‘None, my lord, none that might lead them to such an act. The widow of Gerald the Cooper is in dispute with us over three tuns he willed to us, but you would surely not believe that …’

‘No, we would not believe a cooper’s widow would organise thefts of salt.’ Bradecote permitted himself a small smile.

‘Thefts? We lost but one pack train.’

‘There was another attack, in the same manner, four, no, three days past, upon a cartload of salt bound for the Cistercians at Bordesley, and the two carters were killed.’

‘God have mer

cy upon their souls.’ The abbot crossed himself. ‘We had not heard, my lord.’

‘Is that not unusual, Father Abbot? There are not so many miles ’twixt Wich and here.’ Catchpoll was frowning still, on the verge of one of his ‘thinking faces’ again.

‘You would think so, Serjeant, but all our visitors in the guest hall have been travelling towards Wich these last few days, and with so much to be done before the winter sets in, people are busy at home, not travelling. The news would have reached us in time, and all we can do is pray, for our brothers in Christ and those killed.’

Abbot Robert sighed. As one who was in the world but not ‘of it’, he despaired of the wickedness he saw around him. Hugh Bradecote, realising there was nothing more to be gained from him, made their farewells, and before noon the sheriff’s men were heading north-east towards the Cistercian abbey at Bordesley.

The Archer rubbed chilled hands together and blew upon them silently. Waiting did not worry him. Waiting was part and parcel of his trade. He tore a hunk off the loaf that he had obtained from an old woman, with a heel of hard cheese, in exchange for the hind quarter of a hare he had caught the night before. His needs were simple, and the money that weighed in the scrip he carried meant little beyond the pence it was useful to have for things he could not barter in meat. That the meat was illicitly taken worried him not at all. His attitude to what he might catch in forest and hedgerow was not the same as towards a man’s goose or sheep or pig. If he hunted an animal using his own cunning, if it was a wild beast, all was fair. Then if he took it, he had the right to it.

Blood Runs Thicker

Blood Runs Thicker Vale of Tears

Vale of Tears Faithful Unto Death

Faithful Unto Death Wolf at the Door

Wolf at the Door Hostage to Fortune

Hostage to Fortune Servant of Death

Servant of Death Marked to Die

Marked to Die Ordeal by Fire

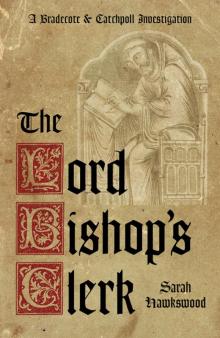

Ordeal by Fire The Lord Bishop's Clerk

The Lord Bishop's Clerk