- Home

- Sarah Hawkswood

Ordeal by Fire Page 10

Ordeal by Fire Read online

Page 10

Chapter Nine

Serjeant Catchpoll was regretting his offer to see Edgar Brewer, for it meant trailing to the northern edge of town, just to the west of the Foregate, and the air held the sultry foreboding of a storm coming. Perhaps the undersheriff’s prayers had been heard, but the serjeant had no desire to be out in the consequences of that success.

Brewer was a tall but stoop-shouldered individual whom Catchpoll assessed to be rather younger than he looked. The serjeant had decided it would be best not to ask the man outright if he knew his wife had possessed the morals of a whore, and so began his conversation with questions about a totally fictitious theft of a barrel from elsewhere in the town. Having opened the interview, he was invited into the brewer’s house. As he did so the brewer drew back slightly and pulled a face. The vestiges of tannery still clung to Catchpoll’s person. The serjeant murmured an apology and made a quip about the less than joyous reception he would be likely to receive at home from his wife, which turned out to be prophetically true. From this it was simple enough to steer the brewer into talking about his late spouse.

‘You must miss her,’ he commented, noticing the unnatural tidiness of the chamber, for the home of a widower of recent date. It bore all the signs of habitation by a house-proud woman, excepting a dirty knife that lay beside a cheese with an irregular chunk cut from it, and a broom rested at a drunken angle beside a heap of dust and old rushes that had got no nearer being swept out than being gathered in one place, as though the sweeper had left in a hurry, with the work half done. Edgar Brewer shook his head, and Catchpoll was caught wondering if he was refuting the idea or was being doleful.

‘My poor Maud. Such a beauty she was, and with a laugh like little tinkling bells. The place is not the same without her.’ He sighed, rather dramatically in Catchpoll’s opinion.

‘A very well-favoured woman as I recall, and very popular.’ Catchpoll did not say with whom, and watched the brewer closely. For an instant he thought he saw a flicker of displeasure cross the man’s face. He risked delving deeper. ‘Very lucky to have such a woman as a faithful helpmeet.’ There was just the slightest stress on ‘faithful’.

This time the change of expression was more definite.

‘Did you know her, yourself, Serjeant?’

Catchpoll caught the inflexion. Brewer had at least had suspicions of his wife, then, if no more. Their eyes met.

‘Not better than being able to say “good morrow” in the street, Master Brewer, but I am not blind.’ Read into that what you will, thought Catchpoll. His attention was suddenly drawn to a basket of washing on a stool by the rear door. Here were further signs of domesticity; everything was neatly folded, and with a repair clearly newly and tidily darned. It might be that Brewer was simply paying a woman to do his washing, though few would then do repairs, or clean house so well. The central hearth was swept and with a fire laid ready to light, but with no sign of cooking. By this hour there should be pottage bubbling away, even if it had been made and set to boil by a wench from elsewhere, as at the silversmith’s. The brewer clearly got his sustenance, if nothing else, by another hearth. So there was a replacement for Maud Brewer in the offing, was there? He returned his gaze to Edgar Brewer.

‘I don’t think I can be of any more help to you, Serjeant, when it comes to missing barrels,’ said the man slowly, keeping eye contact. ‘Good luck with hunting your thief, and if I lose any of mine I will, of course, be sure to tell you straight away.’ He made to show Catchpoll to the door, and the serjeant did not demur. On leaving, he decided that Maud Brewer’s demise, which had occurred when he and the sheriff had been absent, warranted further investigation, whether or not her husband was currently about with flint and steel. Just because they were hunting down one criminal did not prevent him taking interest in other crimes, and murder was murder.

He did not report to Hugh Bradecote, leaving him to his ablutions, and so headed straight for his own cooking-pot and hearth, but just before entering his home he halted and knocked instead next door, at the cooper’s. The man’s youngest son opened the door, and smiled up at him, recognising the neighbour. Catchpoll, seeing that the meal would shortly be served, made his apologies to the mistress of the house with much more sincerity than most got from him, and requested a few words with her husband. She indicated his presence out in the yard that separated work from dwelling, and Catchpoll found him with a pail of water washing his muscled forearms and sweat-stained face.

‘Evenin’, Will. Hot work today.’

William the Cooper blew the water from his top lip and nodded, sending droplets of water from the wet hair hanging over his forehead.

‘Come on a friendly visit, eh? Either your good wife has cast you out and you need a meal, or you are after information.’

‘It’s a cynical man you are, Will,’ grinned Catchpoll, ‘and it’s the information. You have plenty of contact with the brewers, so I was wondering if there was any gossip about the death of Maud Brewer.’

‘Plenty of gossip while she was alive, surely,’ answered Will, with a wicked smile. ‘I could keep you here all evening with tales of what she got up to, and with whom.’ He sniffed. ‘Edgar Brewer is an odd sort of man. Very quiet for one of his trade. His wife died in a fall, as I heard. No interest to you there, though he’s not the broken-hearted widower you might imagine. Of course, how he remained ignorant of his wife’s reputation, or lack of it, remains a mystery, but despite outward shows of grief he seems very settled, and has his feet under the table of Widow Fowler. Not a woman you’d pick for her looks, but maybe he wouldn’t want that second time around.’ Will cast an anxious eye indoors, where his wife was gesticulating.

Catchpoll saw the look on the cooper’s face, and clapped him on the back. ‘My thanks, friend. I’ll not keep you from table, not when your wife will tell mine and I’ll be on bread and dripping for delaying you.’ He smiled, nodded amiably at the harassed housewife as he came back through the house, and saw her wrinkle her nose and frown a little as he passed her close. He went home to his own repast, hoping that the inviting smell that greeted him would mask any lingering foul odour. It did not, though if scathing words alone could cleanse him, he would have been more fragrant very swiftly.

The storm was taking its time brewing. A waning moon peeped cautiously and sporadically from behind scudding clouds, bathing Worcester with deep dark and ghostly silver by turn, though in the narrow street the light scarcely reached. There came rumbles of distant thunder, giving warning of the approaching army of raindrops, but then they ceased. A dog was howling, but it would have been difficult to pin down where. The sound of footsteps, firm and purposeful, reverberated from the walls of the buildings to either side of the narrow thoroughfare, and a dark figure headed eastward along Cokenstrete. The wind whipped the black cloak around the muttering form, which half stumbled and slackened its pace. Pale hands drew the hood more securely over the head and then held the cloak from flapping. In the all-enveloping blackness the dwellings looked much alike and the search for one particular house was unexpectedly difficult. A man emerged from a narrow alley, head down and fumbling with his clothing. He almost collided with the person in the cloak. The pair performed an odd sequence of sidesteps like a bizarre dance as they tried to avoid each other, and the fumbling man passed by with a mumbled apology.

The cloaked figure made its way slowly along the street, peering at the buildings on one side only, and came to a halt. The moon was now totally obscured and the figure became almost invisible. There was a sudden flash as a fork of lightning zigzagged to earth somewhere beyond the far bank of the river. Taken by surprise, the lone mutterer looked up and, for a fraction of a moment, the face was illumined, ghoulishly pale in the white light. It was followed in a moment by a sharp crack of thunder like an enormous whiplash of sound, and proved that the storm had crept up on the town and was already almost overhead. The figure made the sign of the cross, as if to deflect the wrath from the heavens, and stood, clearly

uncertain, looking up and down the street. Then the rain began; slowly at first, with great drops pitting the trodden earth and scattering like the shards of broken glass. The house seeker gazed heavenwards, and then clearly thought better of the nocturnal visit, turning back the way they had come with long strides, stopping for a moment to peer into the darkness of the alley whence the man had emerged.

In the alley shadows, the girl covered her ears and trembled at the sound of the thunder. She too then crossed herself as if the noise were the wrath of God, and directed against her. She did not like plying her trade in the dark, for if the risk of public discovery was less, the risk to her life was greater, and Huw hated being left alone in whatever bolt-hole she had found them. For all that, the men who were busy making money by day had time to spend it in the hours of darkness, and so here she was. She had seen the strange, sinister figure, whose ghostly face had been unknown to her, ‘dance’ with her most recent client and had shrunk back into the shadows, fearful. Now the storm sent her scuttling to the dry security of the stable loft where she had left her brother nestled in sweet hay, and where, curled beside him, she could banish the harsh realities of what she had to do.

Serjeant Catchpoll had not taken much notice of the weather, warm and dry as he was in his own home, and with a good meal inside him. His slumbers had only briefly been interrupted when his wife had woken with a start at the first clap of thunder, and thereafter hidden her head beneath the blanket. He arose, therefore, as refreshed as the dawning day itself, and was about his business in good humour. As he approached the castle gate he saw Drogo the Cook letting himself out of a house further up the street, and sniffed and pursed his thin lips. That was something he had heard no whisperings about. He increased his pace to come up beside his friend.

‘You old dog, Drogo. How long have you kept that little secret?’

Drogo did not look well pleased. ‘Long enough, and I’d be grateful if you’d let it stay a secret. She’s a good woman, Widow Bakere, and don’t deserve her name being dragged into gossip. Aye, and she’s a fine baker too.’

‘So you were just helping her get her buns to rise, eh?’ Catchpoll could not resist the lewd jest. ‘There’s scope for a fine riddle there, you know.’

‘And if you concoct one it will be your teeth, not a loaf, that’s rammed down your throat.’ Drogo was clearly put out, and Catchpoll clapped him on the back reassuringly.

‘No fear, Drogo. It’s none of my concern. Keep your warm Welsh widow and good luck to you.’

They parted in the bailey; Drogo headed to the kitchens and Catchpoll to the guardroom, and sometime thereafter to wait upon the undersheriff. He found him sweeter smelling than the previous evening, but hardly well rested.

‘Good morning, my lord,’ opened Catchpoll, cheerily, noting the heavy eyes and deep shadows around them. ‘Dipping deep with the castellan were we?’ He had good reason to know this was not the case, but kept the foreknowledge to himself.

‘No, Serjeant, “we” were not. In the course of the night there was another fire.’ Bradecote paused, as Catchpoll’s face registered unfeigned horror.

‘But nobody called me,’ the serjeant bemoaned, shaking his head.

‘Correct. That is because they called me instead. The good news, Catchpoll, is that this particular fire-raiser was a bolt from the heavens. The bad news is that one of the watch – and I am glad to see you have been sending out patrols through the night – thought any fire worthy of rousing me from my bed, and in truth, being a potential danger as great as one set by man, I suppose it was not a bad thought. The long and the short of it is that Worcester boasts less of one alehouse, and I have a head that feels as though there’s a cleaver stuck in it.’

‘Which alehouse?’ Catchpoll homed in on the most important information, and exhibited no sympathy for his superior’s state of ill health.

‘The one with the sign of The Goose by the town wall. Nobody was killed, though there was considerable damage and many barrels lost, mostly to the fire. I could not vouch for a few not being rolled away having been “rescued”. It took some time to put out, despite the rain. The roof was good and wet and is sound apart from the hole where the lightning struck, but it destroyed much of the taproom. It will not serve the thirsty within for some time.’

‘More’s the pity, then, for he sold good ale and kept out of our way … few fights or such.’ Catchpoll was silent for a minute, and then continued. ‘Talking of ale, I went and saw Edgar Brewer last evening, before it rained. We should have been told of that death, the wife’s that is, but with the sheriff and my lot up beyond Bredon, and nobody raising a cry because it had the appearance of accident, well, it slipped through the net.’

Bradecote frowned, wishing his head were clearer. ‘You mean, it was not an accidental death at all?’

‘Oh, the husband, he killed her. I would lay you odds on that. Whether we find out how and whether we can prove it is another thing, being this late after the event, but I could feel it.’

Bradecote raised his eyes heavenward. ‘Holy Virgin preserve us, you are going to give me the “mystic serjeant” act now, I presume. All intuitive powers and subtlety. You’ll want incense burners and chanting priests next.’ He was not in a good mood.

Catchpoll prickled at the sarcasm. ‘No, my lord, there’s nothing mystic about it, just the better part of twenty years’ experience as sheriff’s serjeant and the fact that more killings are domestic than anything else. All I claim is years of doing the job, and doing it thorough. Maybe you’ll have it one day.’ The barb in the comment was obvious enough. The amity that had woven between them was still fragile enough to be torn by the pressures of the case.

‘Does it mean that he rises as a suspect for our fires?’ The undersheriff had too great a headache to rise to the insult, but kept his response clipped.

‘That is not certain, my lord. They could as easily be two different things entirely. Mind you, if we keep a watch on Master Brewer, we will either be able to catch him in the act or discount him; and I will do some investigating as to what really happened back in June.’

Bradecote shook his head, partly in refusal and partly to try and clear it of the muzziness. ‘No, I cannot spare you from the fire-setting case. That must take priority over a two-month-old murder that nobody reported as murder anyway.’

‘It’s not taking me from the case if they are linked.’

‘And it is if they are not, Serjeant. We are going to have enough trouble sorting this out before the sheriff returns, and I don’t want to have to tell him that Worcester is in ashes but you have solved a domestic murder.’

Catchpoll bit a lip, meditatively. ‘That’s fair enough, my lord, but what if I select a likely lad from among the men-at-arms to keep a watch on Brewer and do a little probing? He’d be less obvious than me, even if less wily. It gives us the chance to nab Brewer if he sets out with fire in mind without keeping us from other trails. It’s how I started in this line, and I do have a candidate in mind. As for the murder alone, well, if you give me the odd hour over the next few days so I can speak to the neighbours and the local priest, then I think we will soon know if my hunch is right.’

‘Why the priest?’

‘Because when someone dies he is the first person called by the family. They see a lot of bodies in their vocation, and notice things without knowing. Yes, if you want to know about a corpse, ask their priest.’

Catchpoll’s chosen man was one Walkelin, a well-set young man in his early twenties with a shock of ginger hair, a slightly turned-up nose and an open, innocent expression. Bradecote was at first surprised by the choice; the man-at-arms did not look particularly promising, but when he was briefed on his task his questions showed that appearances were very deceptive.

‘Don’t you worry, my lord. Young Walkelin will do well enough, and better than many. He’s a bright lad, and I’ve noticed he has a good eye for detail and a good memory. He will make mistakes here and there, but he won’

t make the same one twice. It’s a pity about the hair, of course, but you can’t have everything … the colour doesn’t really make for blending in and being forgettable.’ Catchpoll shook his head at the errant hair. ‘I have been thinking for some time he would be worth training up for when I’ve no longer a care to go chasing round the shire.’

‘Intimations of mortality, Catchpoll?’

The serjeant gave a puzzled look, and Bradecote explained.

‘You have an idea that you won’t live forever.’

‘None of us does that. We all reach the end at some point. But you won’t go before your time comes,’ Catchpoll replied with perfect seriousness.

‘And murder victims?’

‘Ah.’ Catchpoll paused. ‘Their time came earlier than expected.’

Walkelin was sent to his duties fired with enthusiasm and dreams of glory, and undersheriff and serjeant spent the rest of the forenoon in unprofitable attempts to make any advance in the hunt for the fire-setter.

‘It’s no use,’ sighed Bradecote, rubbing his hand to and fro across his jaw ruminatively, ‘I still say we’re just doing a May dance. Every suspect we raise we then immediately discount, and no linking motive appears either. Why anyone should set fire to Master Ash’s workshop eludes us completely. Nobody seems to dislike him. You’d as well say the fire-raiser didn’t like the shape of the building. When we get to the Corviserstrete fire we cannot tell whether the intended victim was the glover, the old woman, the carpenter or the plot on which the buildings stood, and our suspects have been Mercet, because you dislike him—’

‘And he is an evil guilty bastard, my lord. Be fair.’

‘And he is, as you say, an evil and probably guilty bastard, Simeon the Jew because he is an unknown quantity, and Edgar Brewer because his wife was a whore and you have decided that he killed her, despite any proof. Then there is the unknown lordly man with soft-leather gauntlets and badly burnt hands who visited the old healing woman.’ He ticked them off on his long fingers. ‘And your friend Drogo, who is innocent because you say so.’ Bradecote shook his head, miserably. ‘You know, I hate to say this, Catchpoll, but I have an awful feeling that what we need to get further is another fire.’

Blood Runs Thicker

Blood Runs Thicker Vale of Tears

Vale of Tears Faithful Unto Death

Faithful Unto Death Wolf at the Door

Wolf at the Door Hostage to Fortune

Hostage to Fortune Servant of Death

Servant of Death Marked to Die

Marked to Die Ordeal by Fire

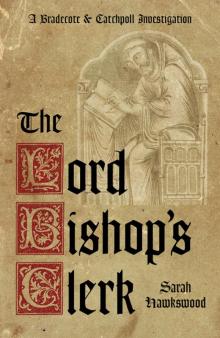

Ordeal by Fire The Lord Bishop's Clerk

The Lord Bishop's Clerk